Oregon’s minimum wage workers rang in the New Year with a raise. At $9.10 an hour, the state now has the second highest minimum wage in the country. Add in payroll taxes and benefits, such as paid time off, and the typical minimum wage worker in Oregon costs an employer about $12.75 an hour.

People pushing a higher minimum wage say that it would lift Oregon families out of poverty. A breathless press release from the state’s labor bureau claims that the latest bump in minimum wage will boost Oregon’s economy with $20 million of additional consumer spending out of thin air. Opponents argue that Oregon’s ever increasing minimum wage leads to layoffs of low-wage employees and may lead some firms to close-up shop.

In fact, both sides are right about the direction of the impact, but a bit hyperbolic about the size. So the question is really one of trade-offs: Do the additional benefits exceed the additional costs?

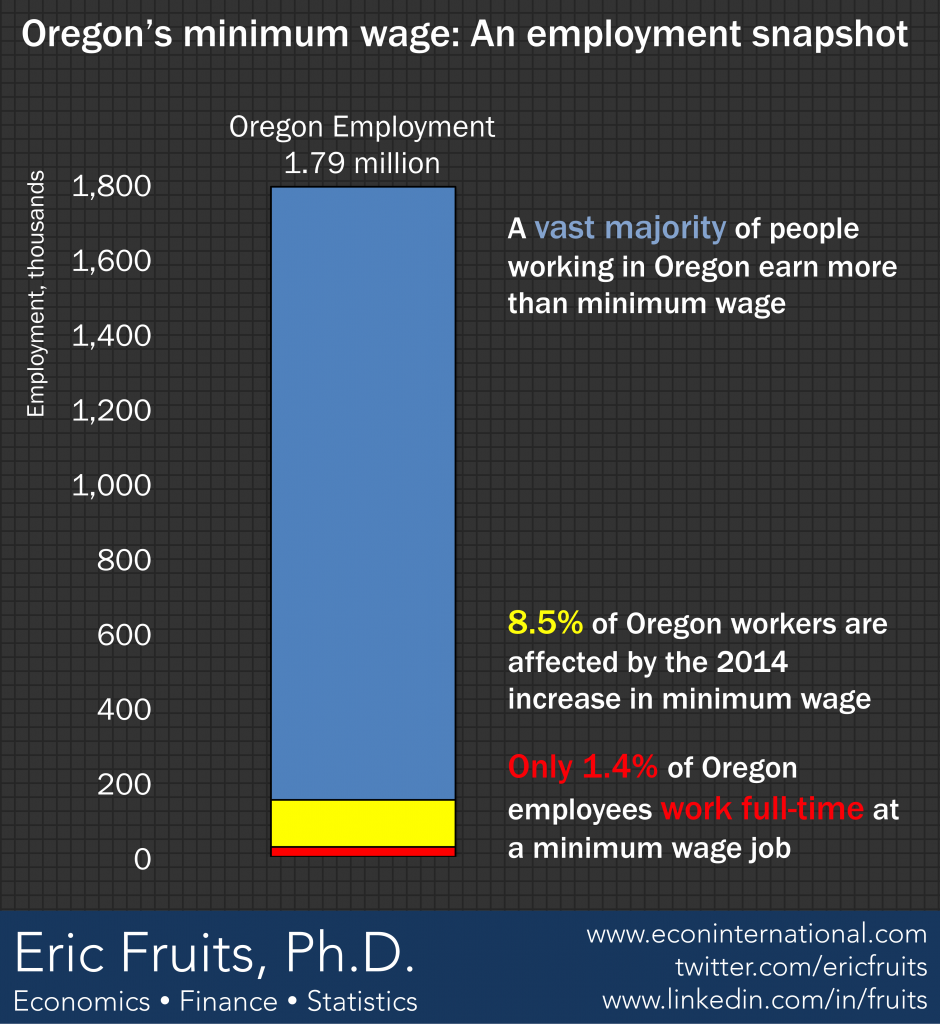

First, let’s look at who earns the minimum wage. The figure above shows a recent employment snapshot for the state. The Oregon Employment Department estimates 149,700 people are affected by this year’s minimum wage increase in one or more of their jobs. That amounts to 8.5 percent of Oregon employment. The number includes people who earned anything less than $9.10 an hour last year and includes anyone who earned minimum wage in any job. So, a teacher who spends the summer months working at a minimum wage job would be included in the count of minimum wage workers reported by the state’s employment department.

Very few workers rely on the minimum wage as their sole source of income. The Employment Policies Institute calculates that less than 1.4 percent of Oregon employees work full time—35 hours or more—in a minimum wage job. The minimum wage work force is a part-time workforce. The share of the population that relies entirely on minimum wage work to support a family is a tiny sliver of the state. In fact, in the U.S., in 8 out of 10 households with children and in which someone earns minimum wage, the minimum wage job accounts for less than 20 percent of total household income. That is, in most cases, the minimum wage job provides a small supplement to income earned from higher paying jobs.

There is some evidence that raising the minimum wage could improve incomes for the working poor. New research suggests that an increased minimum wage could increase family incomes for those at the lower end of the income distribution (in the bottom 15 percent). On the other hand, the impacts are tiny. Using the numbers provided in the paper, it looks like Oregon’s recent minimum wage increase would boost the average family income for this group by less than $3 a week.

On the employer side, its not clear that raising the minimum wage has a huge impact on hiring, firing, and layoff decisions. Especially when the increase is as small as Oregon’s 1.7 percent bump this year. That’s because employers often have many options in the face of higher wage costs. They can raise prices, cut benefits, reduce profits, and invest in technology that boosts labor productivity. While automated fast food ordering may take away a job, it also increases the productivity of the workers that remain.

Indexing the minimum wage to allow for annual increases is perfect politics. When else can a politician take credit for giving someone a pay raise? They can trot out a sympathetic single parent who is better off from the slightly bigger paycheck (if they don’t lose it all in taxes or reduced public assistance).

Even better, an ever increasing minimum wage is a policy where you don’t see the victims. You don’t see the employer who can’t justify paying $12.75 an hour for someone with no experience. You don’t see the teenager who can’t get a job because no one’s willing to pay that kind of money for someone who has no experience or track record.

Oregon unemployment for 16–19 year olds is 26.6 percent. That’s about 3–4 percentage points above the U.S. average. And, it’s not that our teens are lazy. Labor force participation for that age group in Oregon is about the same as the U.S. average. Our kids want to work, but they can’t get the work.

The take away:

Raising the minimum wage makes people who get the raise, and their families, better off. But, just a little. In fact, the weekly amount of the raise amounts to less than the price of a frozen pizza. Employers are slightly worse off, but they have many ways to adjust so that the impact of any annual increase in the minimum wage would be imperceptible. At the same time, Oregon’s high and ever increasing minimum wage puts our younger workers in a Catch-22: They need experience to justify their compensation costs, but they can’t get experience because they cost too much to employ.

Originally published by Oregon Business.